I still have a few of my old college textbooks—physics, statistics, calculus, and such.

They’re the same books I had on the first day of class, but my understanding and use of them has changed. I internalized some concepts —go ahead, ask me the rate of acceleration due to gravity; I can still quote it some 40 years later. But memory is neither perfect nor comprehensive. Now and then I would pull a book out to check my memory and make sure my “internalized” knowledge was still holding water.

Same book. Same content. Same knowledge. Different function.

I don’t mean to trivialize the inspired Word of God in any way, but how we use the Bible should change in a similar way to how the use of a textbook changes over time.

On day one, the book is meant to introduce and explain. There are exercises to measure understanding and encourage practical application of what’s being learned. (Sadly, this step is not always part of our early study of the Bible.)

But, as Paul says, we are not meant to be “milk drinkers” for our entire lives. At some point we are to be meat eaters. That implies maturity in faith, a growing understanding, and an internalization of the concepts captured in Scripture. We should be going back to Scripture to test what we learn and especially what is revealed to us by the Holy Spirit.

Sadly, for many, the Bible has become less a formational text and more a novel—something to be read as a great story rather than a grand lesson. Scripture records a story we focus on, while the One at the center of that story is waiting for us to encounter Him.

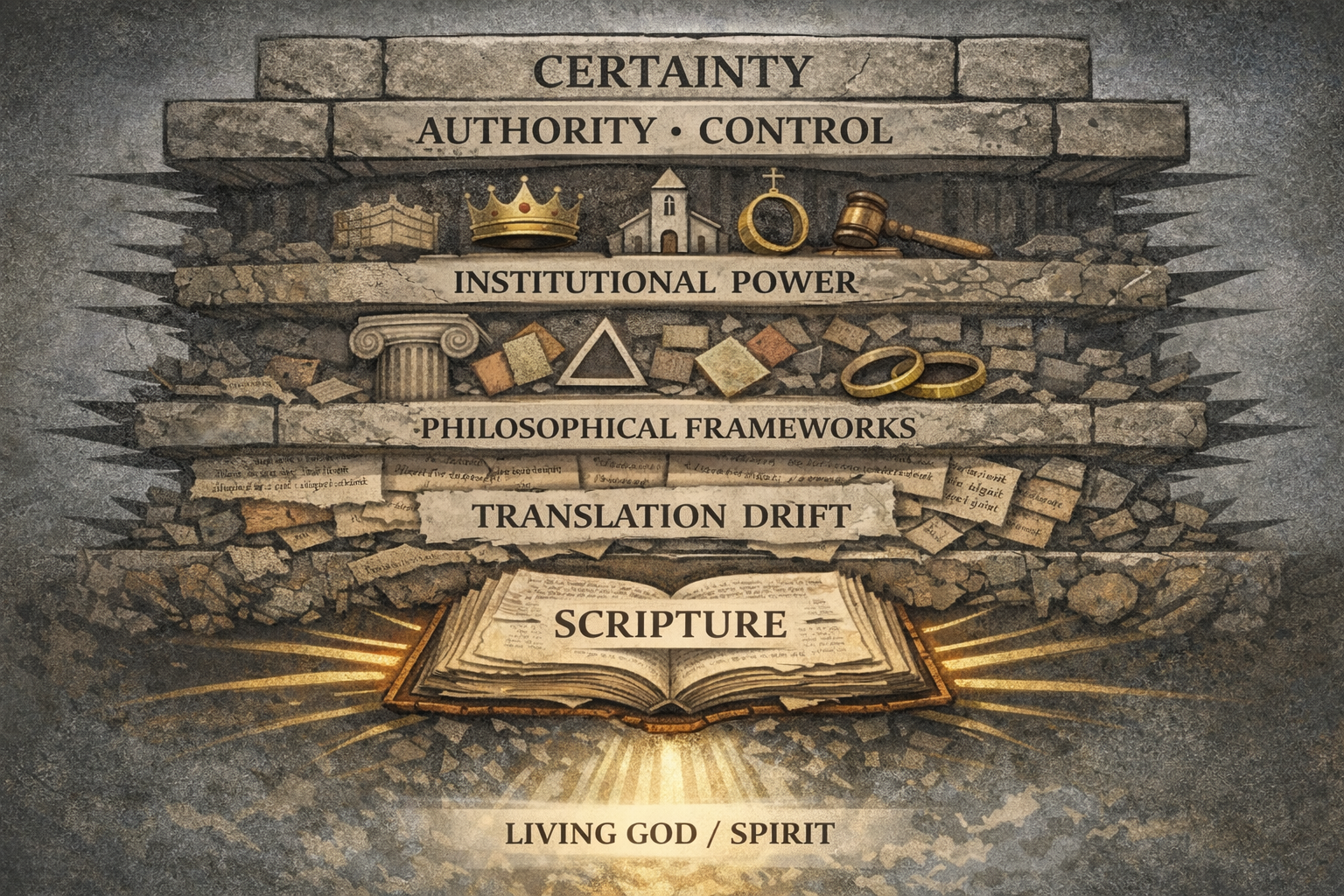

Finding God in Scripture is becoming increasingly difficult. There are significant pressures on the text, on its meaning, and on the lens through which we read it. Far too many of us approach the Word with certainty built on a foundation of folly—a pile of distractions and distortions that has been growing for two to three millennia.

Just a few of the pressures on Scripture:

1. Translation and Drift – In some cases, there are no perfect word-for-word or concept-for-concept matches between Hebrew/Greek and English. Something is lost, shifted, or shaded in the process. Even when translated faithfully, our language has drifted over the centuries, with words having lost their original meaning.

2. Backward Pressure – We read 2,000-year-old text through modern eyes, demanding it satisfy a sense of reality and skepticism it was never meant to bear.

3. Neglected History – We often forget that there were thousands of years of human history before the first book of the Bible was written. The Bible starts with the creation story, but the text itself enters a world already well underway. It assumes many social realities we like to pretend it creates—marriage, slavery, kings, polygamy—and seeks to address those realities without providing detailed “origin stories” for them.

4. Shrinking God – God is bigger than our imagination. Yet I often read theologians who doubt the virgin birth, the flood, Jonah’s time in the fish, and other accounts, testing them against our limited understanding of the natural world while forgetting that God is supernatural. Some want to believe that once God created the universe, He somehow became constrained by His own creation.

5. Desire to be God – We want to know what God knows. We expect detailed explanations and logical behavior so we might understand Him. Doubt me? Go read Genesis 3 again. We cannot understand God. We cannot be God.

6. Invasion of Philosophical Thought – The concepts of Plato, Aristotle, and other philosophers have all left their fingerprints on Christian thought. Many of us refuse to read Scripture without that baggage quietly shaping what we see.

7. The Imperial Church – The merger of church and empire under Constantine introduced a hybrid way of handling Scripture and inverted the concept of “church.” Power and authority became prized over humility and surrender. Where Scripture left tensions or unanswered questions, councils, popes, and emperors spent centuries manufacturing certainty the Word itself does not offer.

There is one more parallel between my physics book and the Bible: both point to a reality; neither is the reality.

If there is a misprint in my physics book and it claims the rate of acceleration due to gravity is 36 ft/sec², that error does not change how fast Newton’s apple will fall. Likewise, an awkward or misleading translation from Greek to English does not—and cannot—change the nature of God. We can experience both the physical world and the living God. Our capacity limits or understanding, not their reality.

When we design an experiment in physics, we do so with appreciation for those who went before us—but we still test against reality. Likewise, as followers of Christ, we respect our teachers, but we seek revealed truth from the Holy Spirit. And we test what we believe we hear from Him against the very Scripture God gave us for that purpose—perfect in its original expression, imperfect in our present handling.

The Bible can point us toward God, but it alone cannot be God to us. God is to be experienced—Scripture itself insists on this.

As we read and use Scripture, we must do so with profound humility, recognizing both our biases and the accumulated weight of thousands of years of man’s interaction with the sacred text.

Image created by ChatGPT. Post edited by ChatGPT and/or Claude.

Search all posts

This Post

Related Posts

Given I operate a non-profit Christian community and other entities, I feel compelled to offer this disclaimer: The opinions expressed on the BFAdams.blog site are my personal opinions. My posts about secular issues are not reflective of the position or leadership of any entity I may be involved with.

And Jesus said to them, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And they were amazed at Him. – Mark 12:17